genre of discourse: gives rules for phrase linkage. Has a unique stake or aim. Examples: dialectical, rhetorical, technical, tragic, comic, artistic, scientific, anthropological.

the philosophical genre of discourse: seeks to discover its own rules, and does not mind "wasting the time" in doing so.

I. The Establishment of Reality

§B. Reality emerges when the referent of ostension in the current phrase is carried over into a different, now current phrase, whose deictic context (the “I”-“here”-“now” nexus) has shifted. There we stand before a red flower, and after some time we move on, we walk around the corner, all the while talking about its color. Maybe by comparing it to other red objects we know. Maybe, if we are adepts in the language of electromagnetic radiation, we will talk about it in terms of wavelength (§61), which is in turn a measure of comparison with all other visible objects.

§C. By this point in our walk, with the flower no longer in sight, “red” has become a name. See how it, as name, perdures across significations, exhibiting formal rigidity (§60), even as it attracts new significations, regardless how many (§74-5). In the cognitive genre: red like a lingonberry, a fire engine, a fire button; in the exclamatory genre: what I see now in my anger; in the normative genre: that to which our economy ought or ought not aspire (§77-79). But to show the reality of this named thing, we must return to ostension, combining it with the name and the signification we have in mind. Reality is thus established (§65,§82).

§D. —What do you mean, “reality emerges” and “reality is established”? It’s already there. All you have to do is look! (§49) —If you look, how can you tell that you are seeing appearance rather than reality? Is the moon really disappearing, or is it waning? Is there an eclipse? —Because I happen to know a thing or two about astronomy… —On the other hand, if you assume that what you see is real, how can you know which parts to include in that reality that escape your current perspective? How can you say the moon is real, if you know nothing of its dark side? —Again, because of my knowledge of astronomy… —Whose every object, on your understanding of reality, is based on what might turn out to be mere appearance or upon a partial vision of a whole whose complete nature, if revealed, might overturn your concept of what it is that you see (§63). And even if you satisfy yourself with the coordination of these partial glimpses, that coordination would only be possible by the names that persist over time and the significations they gather.

§E. —What about picture of reality, made of simple signs, each of which maps to an element of reality? —But to judge the soundness of the correspondence, you need to compare reality with your picture of it, which requires holding a picture of reality up against…a picture of your picture of reality? And so your judgment of a picture’s goodness rests on the assumption another picture’s goodness (§55)? —But certainly the reality of the object I am pointing to right now is a property of that object, if it is to be, well, real (§47,§67)? —But mere ostension doesn’t suffice (Wittgenstein’s chess king, Philosophical Investigations, §31), nor does adding a description: an empty designator needs to bind these two and situate them in a network of names (§67).

§F. The spontaneous understanding of reality is overturned. The important upshot of this is that reality is not fixed or unitary, but is rather like a phrase — radically open to the future — open to the swarm of significations that attract to a name. (§82,§88) Of course, in being open, reality is also open to doubt: “its assertion is subject to the rules for establishing reality…”(§101). Reality never detaches from the rules of its establishment. And reality is irreducibly plural, a set of lines passing through the single point that is the phrase.

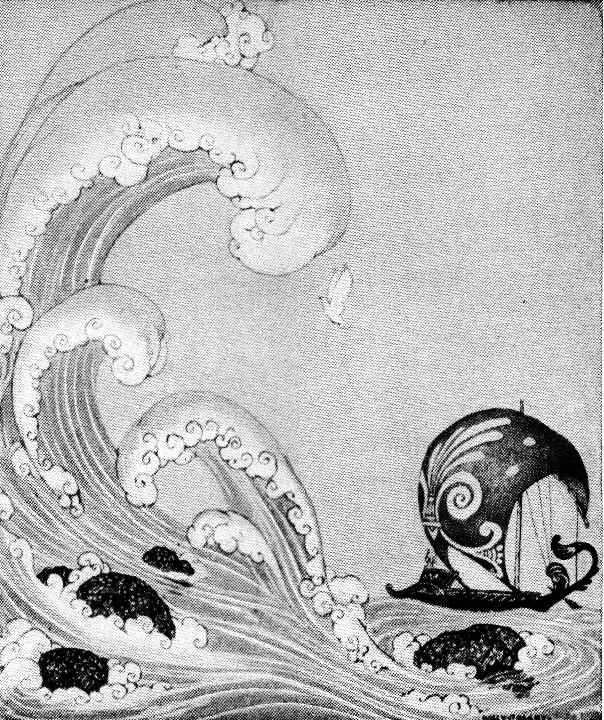

§G. Anaximander Notice. What realities there are begin, in every case, with a phrase, an occurrence, an Ereignis. What of this phrase, this agitated indeterminacy that we wait upon in anxious vigil, what of this, might we say, ἄπειρον?

[Anaximander] declares that what arose from the eternal and is productive of … hot and cold was separated off at the coming to be of this kosmos, and a kind of sphere of flame from this grew around the dark mist about the earth like bark about a tree. When it was broken off and enclosed in certain circles, the sun, moon, and stars came to be. (pseudo-Plutarch, Stromata 2 = DK 12A10)